When people talk about suddenly remembering old memories, the memories they’re referring to are usually autobiographical or episodic memories. As the name suggests, this type of memory stores the episodes of our life.

Another type of memory that can also be suddenly remembered is semantic memory. Our semantic memory is the storehouse of our knowledge, containing all the facts we know.

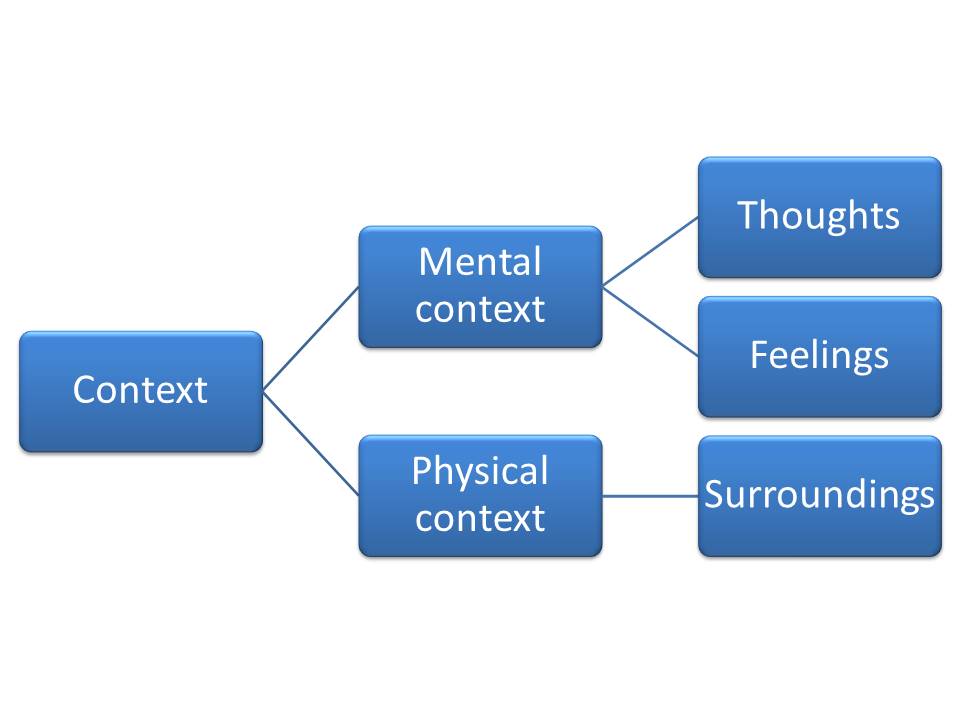

Usually, the recall of autobiographical and semantic memories has easily identifiable triggers in our context. Context includes our physical surroundings as well as the aspects of our mental state, such as thoughts and feelings.

For example, you’re eating a dish at a restaurant, and its smell reminds you of a similar dish your mom used to make (autobiographical).

When someone utters the word “Oscar”, the name of the movie that won the Oscar recently flashes in your mind (semantic).

These memories had obvious triggers in our context, but sometimes, the memories that flash in our minds have no identifiable triggers. They seem to pop into our minds out of nowhere; therefore, they’ve been called mind-pops.

Mind-pops shouldn’t be confused with insight, which is the sudden popping up of a potential solution to a complex problem in the mind.

Thus, mind-pops are semantic or autobiographical memories that suddenly flash in our minds without an easily identifiable trigger.

Mind-pops may comprise any piece of information, be it an image, a sound, or a word. They’re often experienced by people when they’re engaged in mundane tasks like mopping the floor or brushing teeth.1

For example, you’re reading a book, and suddenly, the image of your school corridor pops into your mind for no reason. What you were reading or thinking at the time had no connection whatsoever to your school.

I do experience mind-pops from time to time. Often, I try to search for cues in my context that may have triggered them, but with no success. It’s quite frustrating.

Context and suddenly remembering old memories

It’s long been known that the context in which you encode a memory plays a huge role in its recall. Greater the similarity between the context of recall and the context of encoding, the easier it is to recall a memory.2

This is why it’s better to rehearse for performances on the same stage where the actual performance will take place. And why spaced learning over a period of time is better than cramming. Cramming all the study materials in one go provides minimal context for recall compared to spaced learning.

Understanding the importance of context in memory recall helps us understand why there’s often a feeling of suddenness involved in recalling old memories.

We encoded our childhood memories in one context. As we grew up, our context kept on changing. We went to school, changed cities, started work, etc.

As a result, our current context is far removed from our childhood context. We rarely get vivid memories of our childhood in our present context.

When you return to the city and the streets you grew up in, suddenly, you’re placed in your childhood context. This sudden change of context brings back old childhood memories.

Had you visited these areas frequently throughout your life, you probably wouldn’t have experienced the same level of suddenness in recalling associated memories.

The key point I’m trying to make is that the suddenness of memory recall is often associated with the suddenness of context change.

Even a simple context change, like going out for a walk, can trigger the recall of a stream of memories you didn’t have access to in your room.

Unconscious cues

When I tried to look for cues in my context that may have triggered my mind-pops, why did I fail?

One explanation is that such mind-pops are completely random.

Another more interesting explanation is that these cues are unconscious. We’re simply unaware of the unconscious connection that a trigger has with a mind-pop.

This is further complicated by the fact that a significant portion of perception is also unconscious.3 So, identifying a trigger becomes twice as hard.

Say a word pops into your mind. You wonder where it came from. You cannot point to any trigger in your context. You ask your family members if they’ve heard it. They tell you that this word came up in an advertisement they saw 30 minutes ago on TV.

Sure, it may be a coincidence, but the more likely explanation is that you unconsciously heard the word, and it stayed in your accessible memory. Your mind was processing it before it could transfer it into long-term memory.

But since making sense of a new word requires conscious processing, your subconscious vomits the word back into your stream of consciousness.

Now, you know what it means in the context of some advertisement. So your mind can now safely store it into long-term memory, having attached it to meaning.

Repression

Repression is one of the most controversial topics in psychology. I feel it’s worth considering when we’re talking about the sudden retrieval of memories.

There have been cases where people had completely forgotten instances of childhood abuse but recalled them later in life.4

From a psychoanalytic perspective, repression occurs when we unconsciously hide a painful memory. The memory is too anxiety-laden, so our ego buries it in the unconscious.

I want to narrate an example from my life that I think comes closest to this concept of repression.

A friend of mine and I had a terrible experience during our undergrad years. Things were better for us when we were in high school and later when we enrolled in our Master’s. But the undergrad period in between was bad.

Years later, while I talked to him on the phone, he told me something that I could totally resonate with. He talked about how he had forgotten almost everything about his undergrad years.

At that time, I wasn’t even thinking about my undergrad years. But when he mentioned it, the memories came flooding back. It was as if someone left open a tap of memories in my mind.

When this happened, I realized that I, too, had forgotten everything about my undergrad years until this moment.

If you were to turn the metaphorical pages of my autobiographical memory, the ‘High School page’ and the ‘Master’s page’ would be stuck together, hiding the pages of undergrad years in between.

But why did it happen?

The answer probably lies in repression.

When I joined my Master’s, I had a chance to build a new identity on top of a previous, undesirable identity. Today, I’m carrying forward that identity. In order for my ego to successfully carry forward this desirable identity, it needs to forget the old undesirable identity.

Therefore, we tend to remember things from our autobiographical memory that is congruent with our current identity. A conflict of identities often marks our past. The identities that win will seek to assert themselves over other, discarded identities.

When I talked to my friend about our undergrad years, I remember him saying:

“Please, let’s not talk about that. I don’t want to associate myself with that.”

References

- Elua, I., Laws, K. R., & Kvavilashvili, L. (2012). From mind-pops to hallucinations? A study of involuntary semantic memories in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 196(2-3), 165-170.

- Godden, D. R., & Baddeley, A. D. (1975). Context‐dependent memory in two natural environments: On land and underwater. British Journal of psychology, 66(3), 325-331.

- Debner, J. A., & Jacoby, L. L. (1994). Unconscious perception: Attention, awareness, and control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 20(2), 304.

- Allen, J. G. (1995). The spectrum of accuracy in memories of childhood trauma. Harvard review of psychiatry, 3(2), 84-95.