To compartmentalize something means to divide it into compartments or sections. In Psychology, compartmentalization means dividing mental contents into separate compartments in the mind. These mental contents could be thoughts, emotions, feelings, motives, beliefs, memories, personalities, or identities.

Compartmentalization is a natural consequence of how the mind works. By categorizing mental information, the mind can deal with it efficiently. For instance, right now, you’re reading this article. Your thoughts are focused on the topic of compartmentalization. You’ve likely shut off other things you could be thinking about. Your mind has compartmentalized your current mental contents into two categories: “What I should focus on” and “What I shouldn’t focus on”. By doing this, your mind preserves your mental energy so that it can devote it to the task at hand.

Cohesive sense of self

Compartmentalization keeps important things in our awareness and pushes unimportant things out. Our mind has a CEO, our sense of self, that decides where to allocate our mental energy, just like the CEO of a company makes important decisions about where to allocate resources. This sense of self has to manage multiple psychological processes, which usually work together. Even though the different departments of an organization work independently, they have to be connected and integrated.

The organization might collapse if they keep functioning independently with no connection and shared goals.

Similarly, under normal circumstances, the mind can integrate its mental processes. That is, it can execute multiple processes simultaneously or one after the other while maintaining a connection between them. This helps us achieve mental cohesion and a cohesive sense of self.

From integration to dissociation

The mind can achieve integration as long as it can allocate mental energy efficiently to daily tasks. However, when a stressful event occurs, the mind is under pressure. Your mental energy can no longer flow smoothly between tasks.1Gilbert, P. (2013). An evolutionary and compassion-focused approach to dissociation. In Cognitive behavioural approaches to the understanding and treatment of dissociation (pp. 190-205). Routledge. Something has come up that requires a higher-than-normal allocation of mental energy.

Previously, the mind could integrate different mental processes because it could allocate mental energy to them to keep them up and running. Now, it no longer can. It has to devote a considerable amount of mental energy to the stressor that has come up. As a result, integration breaks down.

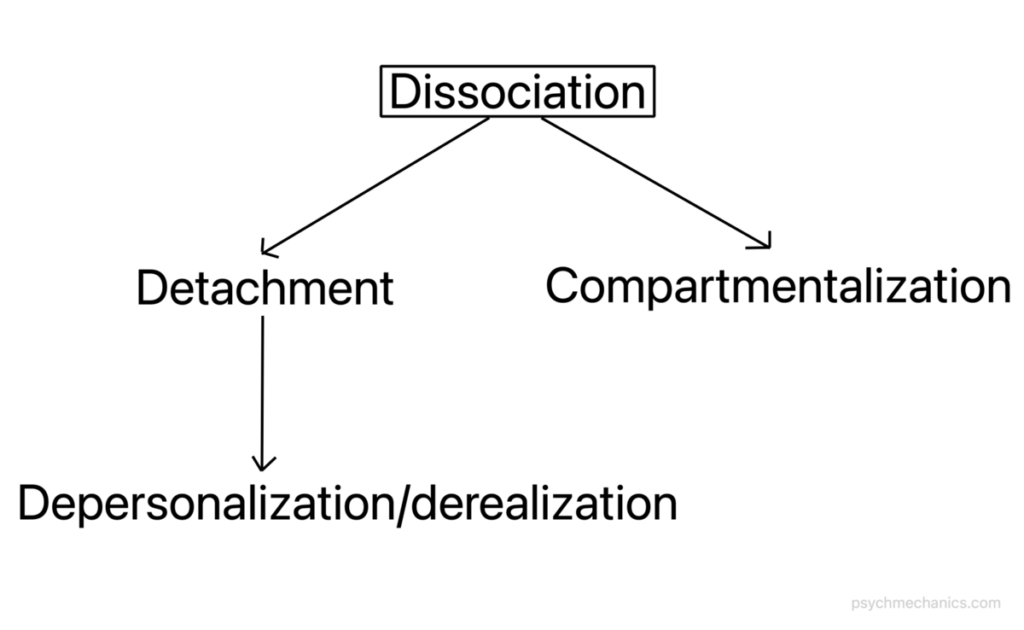

Types of dissociation

Dissociation is nothing but a breakdown of integration. When you experience dissociation, your mental processes and contents get divided. The degree of dissociation depends on the severity of stress.2Bowins, B. E. (2012). Therapeutic dissociation: Compartmentalization and absorption. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 25(3), 307-317. If the stress is mild, dissociation is mild, and you might find yourself daydreaming or zoning out. If the stress is severe, as in a traumatic event, the dissociation is severe and can range from depersonalization/derealization to Dissociative Identity Disorder.3Brown, R. J. (2006). Different types of “dissociation” have different psychological mechanisms. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(4), 7-28.

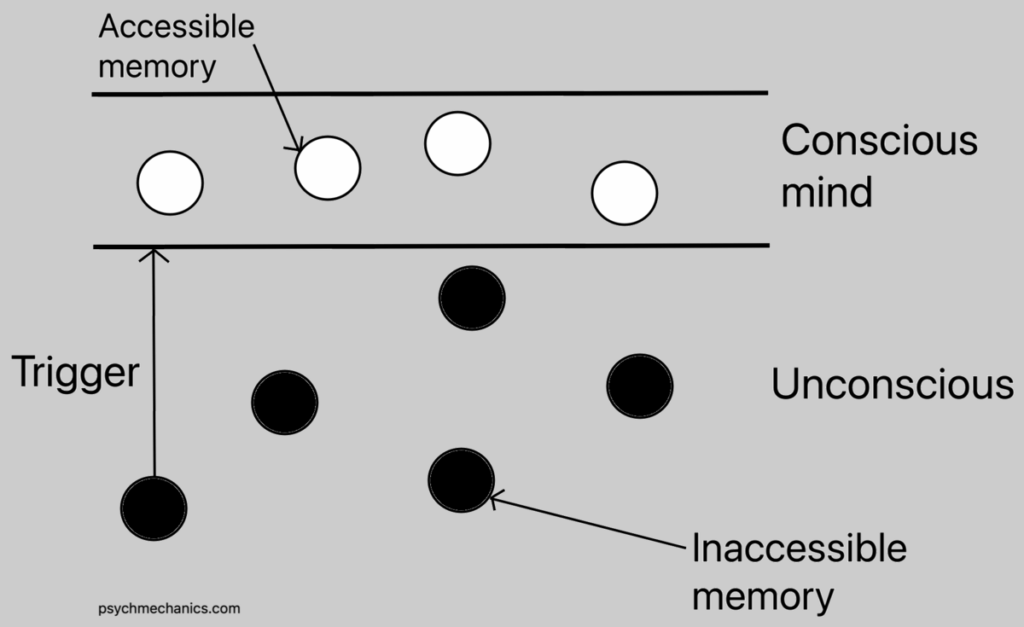

There are two main types of dissociation- detachment and compartmentalization. Detachment is separating yourself from a negative event and its associated emotions. Compartmentalization organizes information about a negative event into a separate container of the mind, pushing it out of awareness. You can’t access it with will, but it lingers in your unconscious.

Even though compartmentalization is a broader term, repression is a form of compartmentalization.

Compartmentalization of self-aspects

The best way to understand compartmentalization is to examine how we compartmentalize our personalities or identities. We have multiple identities or selves. Self-aspect is one aspect of them. It is a belief we have about ourselves. Self-aspects can be either positive or negative. We deem some of our self-aspects as more important than others.

| Self-aspect | Valence | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| ‘I am smart’ | Positive | Important |

| ‘I am lazy’ | Negative | Not important |

When you go through interpersonal trauma, especially childhood trauma, where you’re abused or emotionally neglected, you develop negative self-aspects (e.g., ‘I am worthless’). These negative aspects of your identity are painful and associated with negative emotions like guilt and shame. With compartmentalization, the mind locks these negative self-aspects into mental containers that are pushed out of awareness. If these negative self-aspects were kept in awareness, they would consume a bulk of your mental energy to the point that you couldn’t function in day-to-day life.4Kennedy, F. C., Kennerley, H., & Pearson, D. G. (Eds.). (2013). Cognitive behavioural approaches to the understanding and treatment of dissociation. London: Routledge.

As a defense mechanism, some people gather all their positive self-aspects in one container and deem them most important. These positively compartmentalized people tend to have high self-esteem.5Ditzfeld, C. P., & Showers, C. J. (2013). Self-structure: The social and emotional contexts of self-esteem. In Self-esteem (pp. 21-42). Psychology Press. They’ve kicked the container of their negative self-aspects deep into their unconscious. On the other hand, some people aren’t able to do this. The negative experiences they went through define them. For these negatively compartmentalized people, their negative self-aspects are most important.

| Positive compartmentalization | Negative compartmentalization |

|---|---|

| ‘I am smart’ | ‘I am worthless’ |

| ‘I am hard-working’ | ‘I am weak’ |

| ‘I am self-reliant’ | ‘I am unfriendly’ |

| ‘I am trustworthy’ | ‘I am boring’ |

| ‘I am honest’ | ‘I am lazy’ |

The downside of positive compartmentalization

If you ask a positively compartmentalized person about their flaws, they’ll say they have none. They’re not lying. Their mind has hidden their negative self-aspects from them. They’re able to maintain a positive, functional sense of self. They may even be highly successful individuals. However, when a stressful event occurs pertaining to a domain in which they’ve pushed their negative self-aspect under the rug, that negative self-aspect comes out of the rug and flies in their face.

In other words, when triggered by a situation, their negative self-aspect may resurface in their stream of consciousness, causing them significant distress. It takes a while for them to recover from this sense of:

“I’m not who I thought I was.”

An example

Jane is a successful entrepreneur. She works long hours and has ‘hard-worker’, ‘successful’, ‘organized’, and ‘problem-solver’ as her important positive self-aspects under her ‘work self’. However, her ‘social self’ isn’t all that bright. She has negative self-aspects such as ‘difficult to approach’, ‘dismissive’, and ‘cold’ under her ‘social self’. So, she avoids situations where her negative self-aspects are activated (socializing) and is over-invested in her work self, which only activates her positive self-aspects. She has put her social self under the rug because she doesn’t want to face her social flaws. She considers her work self as more important and is a positively compartmentalized individual.

One day, she was invited to a networking event. Her gut feeling was to avoid it, but she knew that the event could lead to opportunities. During the event, she barely connected with anyone, which triggered her. Her negative social self-aspects were brought to the surface of her consciousness. She moved from positive compartmentalization to negative compartmentalization. She couldn’t access her positive self-aspects in this situation where she isn’t working. There’s no connection between her compartments.

As you can see, although positively compartmentalized people tend to have high self-esteem, it rests on shaky grounds. It’s situation-dependent.6Zeigler-Hill, V., & Showers, C. J. (2007). Self-structure and self-esteem stability: The hidden vulnerability of compartmentalization. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(2), 143-159. They’re vulnerable to getting triggered and emotional reactivity because their positive compartmentalization masks their fragile self underneath.

After this incident, Jane concluded that there was something wrong with her and sought therapy.

From compartmentalization to integration

Those who seek therapy are often negatively compartmentalized, or individuals who move from positive to negative compartmentalization as a result of a recent stressful event, like Jane. Therapy aims to bring negative self-aspects into awareness in a safe space to process them. When that happens, a person achieves integration. That is, they have a mixture of positive and negative self-aspects, with a healthy connection between them. They’re happy about their positive self-aspects but are also aware of their negative self-aspects. Since they are aware of their negative self-aspects, they can work on those and manage or change them.

Integrative individuals have moderate levels of self-esteem, but their self-esteem is more stable.7Showers, C. J., Limke, A., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2004). Self-structure and self-change: Applications to psychological treatment. Behavior Therapy, 35(1), 167-184. They’re balanced, secure, and resilient. Most importantly, they have a realistic view of themselves. They’re able to process and grow from their traumatic experiences.

A downside of integration is that it requires considerable mental energy to process multiple contradictory pieces of information about yourself. That is why therapy is hard. In my view, the stabilized self-esteem is worth the cost.