Metacommunication can be defined as ‘communication about communication’.1 In its simplest form, the communication process involves a sender who sends a message to a receiver.

Think of receiving communication as buying a new gadget. The store owner is the sender, the gadget is the message, and you’re the receiver.

If the store owner simply hands over the gadget to you, sans any package, it’s the simplest type of communication. Such communication is devoid of any higher levels of communication or metacommunication.

However, that rarely happens. The store owner will typically give you the gadget with a package, an instruction manual, a warranty, and perhaps some accessories. All these additional things refer to or say something more about the gadget, the original message.

For example, the earphones tell you that you can plug them into the gadget. The instructional manual tells you how to use the gadget. The packaging tells you about the specifications and features of the gadget, and so on.

All these extra things point to the gadget, the original message. All these extra things comprise metacommunication.

Hence, a package of communication and metacommunication helps you better understand the communication.

If you were simply given the gadget without any extras, chances are you would’ve struggled to figure it out.

Similarly, in our day-to-day communication, metacommunication helps us to figure out the communication.

Verbal and nonverbal metacommunication

Since metacommunication is communication about communication, it has the same nature as communication. Like communication, it can be either verbal or nonverbal.

Saying “I care about you” is an example of verbal communication. You can convey the same message non-verbally by, for example, offering your coat to someone feeling cold.

These are examples of communication with hardly any metacommunication involved. There are no higher levels of communication involved. The message is easily understood and straightforward.

If someone says “I care about you” but doesn’t help you in times of need, there’s scope to explore more. There’s reason to go a level higher than what was said (“I care about you”) and wonder if it meant something else. There’s reason to look for metacommunication.

The nonverbal metacommunication of “not helping” overrides and contradicts the literal meaning of “I care about you”. The result is that you interpret that “I care about you differently”. Either you think it was a lie or you ascribe some ulterior motive to the person who uttered those words.

Metacommunication adds an additional quality to the original, direct communication. It frames the communication. It can contradict the original message, as in the above case, but it can also support it.

For instance, if someone says “I’m not okay” in a dejected tone, the dejected tone is a non-verbal metacommunicative signal confirming the original, verbal communication.

When we communicate, we instinctively look for these metacommunicative signals to decipher the original signal accurately.

Metacommunication examples: Detecting incongruence

While metacommunication often supports the original communication, it becomes more apparent when there’s incongruence between the signal and the intention of the sender for the signal.

Sarcasm, irony, satire, metaphors, and puns utilize metacommunication to force the receiver to look at the context or metacommunication of what’s being communicated. The metacommunication alters the usual meaning of the message.

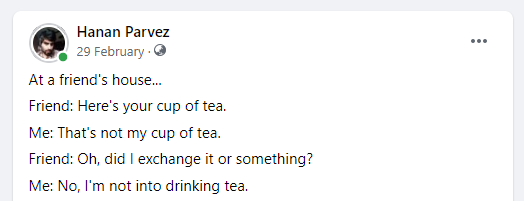

In puns, for example, you have to lay the groundwork or set the context which the receiver can use to understand the pun. Take a look at this pun:

Had I not contextualized the message (“That’s not my cup of tea”) with the subsequent metacommunication (“I’m not into drinking tea”), the receivers would’ve had a hard time understanding the pun.

People often have to say “I was being sarcastic” because receivers failed to pick up the irony or irrationality in what was communicated (verbal metacommunication) or missed the sarcastic tone or smile (nonverbal metacommunication).

As a result, receivers didn’t go above or beyond the message and interpreted it literally i.e. at the lowest, simplest level.

Another common example of metacommunication is saying something in a mocking tone. If a child says to its parent, “I want a toy car” and the parent repeats “I want a toy car” in a mocking tone, the child understands that their parent doesn’t really want a toy car.

Thanks to the metacommunication (voice tone), the child goes beyond the literal meaning of what was said to look at the intention behind it. Obviously, after this interaction, the child will be annoyed at the parent or even think they’re not loved.

This brings us to the types of metacommunication.

Types of metacommunication

You can categorize metacommunication in several complex ways and indeed many researchers have attempted to do so. I prefer William Wilmot’s classification as it focuses on the essence of much of human communication- relationships.2

If we assume that much of human communication has something to say about the relationship between the sender and receiver, we can classify metacommunication into the following types:

1. Relationship level metacommunication

Why is it that if you say, “You idiot” to a friend they’re unlikely to get offended but the same words, when told to a stranger, can be offensive?

The answer lies in a phrase called relational definition. The relational definition is simply how we define our relationship with the other.

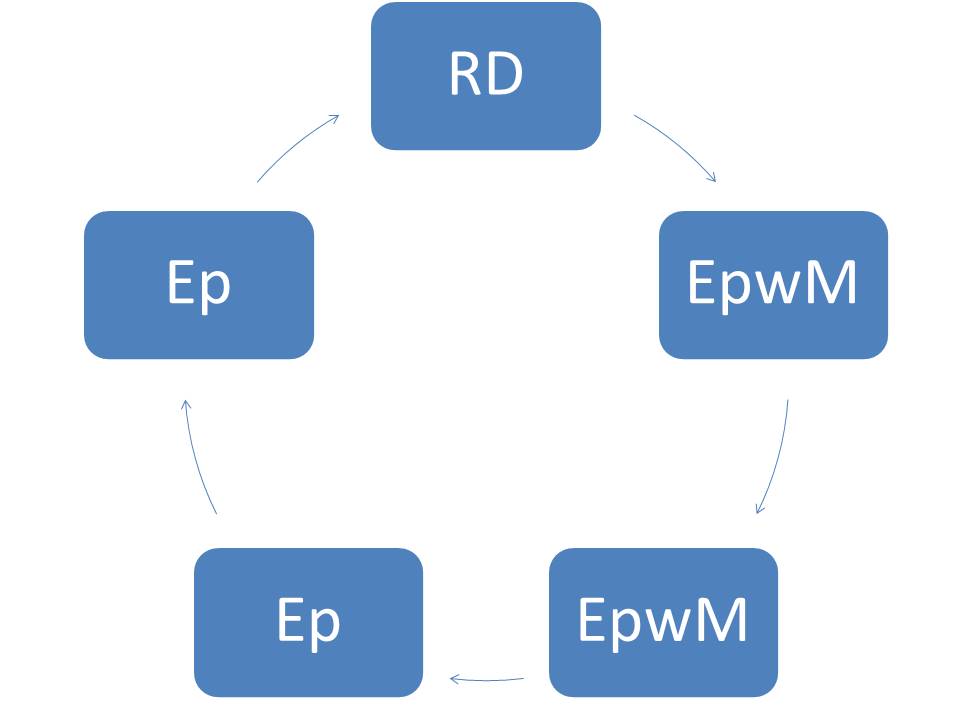

When we interact with others over time, the relational definitions between us and them emerge over time. This emergence is facilitated by a series of metacommunicative and communicative signals. Indeed, these metacommunicative signals sustain a relational definition.

You have a relational definition of “I’m your friend” with your friend. It was built over time when you two engaged in a number of friendly interactions with each other.

So when you tell them they’re an idiot jokingly, they know you don’t mean it. This interpretation is consistent with the relational definition that exists between you two.

Saying the same thing to a stranger, with whom you’re yet to establish a friendly relational definition, is a bad idea. Even if you’re joking, the message will likely be interpreted literally because there’s no relational metacommunicative context to what you said.

The stranger has no reason to think you’re just being friendly. I see this happen so many times. If I’m close to someone, they’ll tell me I can say whatever I want to them. But when the same thing is said to them by an acquaintance, they’re like, “Who is he to tell me this?”

Every person you communicate with, except strangers, has a relational definition in their mind about you.

Metacommunicative signals over time reinforce a relational definition, providing a metacommunicative context for subsequent interactions.

2. Episodic level metacommunication

Relationship level metacommunication, based on a relational definition, happens after several, recurring episodic level metacommunications. You have to reach that stage in the relationship after which the subsequent interactions get contextualized by a relational definition.

On the other hand, episodic level metacommunication is devoid of any relational definition. This type of metacommunication occurs on the level of individual episodes only. It includes all the one-time interactions you might have had with strangers, such as saying, “You’re an idiot” to a stranger.

People have a tendency to infer relational intent from episodic level metacommunications. It’s because that is precisely the function of episodic level metacommunications- to build a relational definition over time.

Episodic level metacommunications are tiny seeds that grow into a relational definition over time.

This means you’re more likely to think that a customer care executive is intentionally not helping you than thinking that perhaps you didn’t explain your problem clearly.

Instead of looking objectively at such conflict situations, we readily focus on intentions because we have a tendency to build a relational definition with every small interaction.

Why?

So we can understand others’ intentions better in future communications after the relational definition is established. This is just the natural way humans communicate. We’re always looking to form relational definitions out of ordinary, episodic interactions.

Ancestral humans weren’t making customer care calls. They were on the lookout for friends and foes (forming relational definitions) while they shared and defended themselves and their resources.

Seeing signals as signals

That we can perceive metacommunication indicates we have the capacity to not only interpret signals but also form some idea about the intention of the sender. We can separate the signal from the sender.

Metacommunication has also been observed in other social primates.3 In fact, Gregory Bateson came up with the term after observing monkeys in a zoo who were engaged in play.

When young monkeys are engaged in play, they display behavior typical of a hostile interaction- biting, holding, mounting, dominating, etc.

Bateson, observing all this, wondered there must be some way in which the monkeys are able to metacommunicate “I’m not being hostile” to each other.4

It may be something in their body language or posturing. Or it may be because the monkeys have had time to form a relational definition of friendliness and warmth.

Being able to see a signal as a signal, instead of blindly responding to it according to its apparent, meaning must have had significant evolutionary advantages.

For one, it provides a window into the mind and intentions of the other person. It also reduces the risk of deception and enables us to keep track of friends and enemies. It builds our relationships on the basis of relational definitions.

We update these relational definitions in the light of new interactions, making our bonds with others stronger or weaker over time.

Improving metacommunication skills

Being good at metacommunication is part and parcel of improving your communication skills.

When you take into account the metacommunicative aspects of communication, you can better frame or contextualize your message. You can deliver your message clearly and interpret messages clearly.

Getting good at detecting discrepancies between metacommunication and communication will help you detect lies, avoid deception, and figure out the motives of people.

The key thing to remember is that communication always happens in a context. Learning to interpret body language, facial expressions, and voice tone won’t take you far if you ignore context.

Another important thing to remember, especially when you’re trying to figure out the intentions of people, is that you should always try to test and verify your assumptions.

References

- Bateson, G. (1972). The logical categories of learning and communication. Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 279-308.

- Wilmot, W. W. (1980). Metacommunication: A re-examination and extension. Annals of the International Communication Association, 4(1), 61-69.

- Mitchell, R. W. (1991). Bateson’s concept of “metacommunication” in play. New Ideas in Psychology, 9(1), 73-87.

- Craig, R. T. (2016). Metacommunication. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy, 1-8.