Do you know what’s the single biggest factor causing problems in relationships? It’s a phenomenon called the fundamental attribution error based on a Social Psychology theory called Attribution Theory.

Before we talk about the reasons for fundamental attribution error, let’s properly understand what it means. Consider the following scenario:

Sam: What’s the matter with you?

Rita: It took you an hour to text me back. Do you even like me anymore?

Sam: What?? I was in a meeting. Of course, I like you.

Assuming Sam wasn’t lying, Rita committed the fundamental attribution error in this example.

To understand fundamental attribution error, you first need to understand what attribution means. Attribution in psychology simply means attributing causation to behavior and events.

When you observe a behavior, you tend to look for reasons for that behavior. The attribution process is called the ‘looking for reasons for a behavior’. When we observe a behavior, we have an inherent need to understand that behavior. So we try to explain it by attributing some cause to it.

What do we attribute behavior to?

Attribution theory focuses on two major factors- situation and disposition.

When we’re looking for reasons behind a behavior, we attribute causation to situation and disposition. Situational factors are environmental factors while dispositional factors are the internal traits of the person doing the behavior (called an Actor).

Say you see a boss shouting at his employee. Two possible scenarios emerge:

Scenario 1: You blame the boss’s anger on the employee because you think the employee is lazy and unproductive.

Scenario 2: You blame the boss for his anger because you know he always behaves like that with everyone. You conclude the boss is short-tempered.

Correspondent inference theory of attribution

Ask yourself: What was different in the second scenario? Why did you think the boss was short-tempered?

It’s because you had sufficient proof to attribute his behavior to his personality. You made a correspondent inference about his behavior.

Making a correspondent inference about someone’s behavior means you attribute their external behavior to their internal traits. There’s a correspondence between the external behavior and the internal, mental state. You made a dispositional attribution.

Covariation model

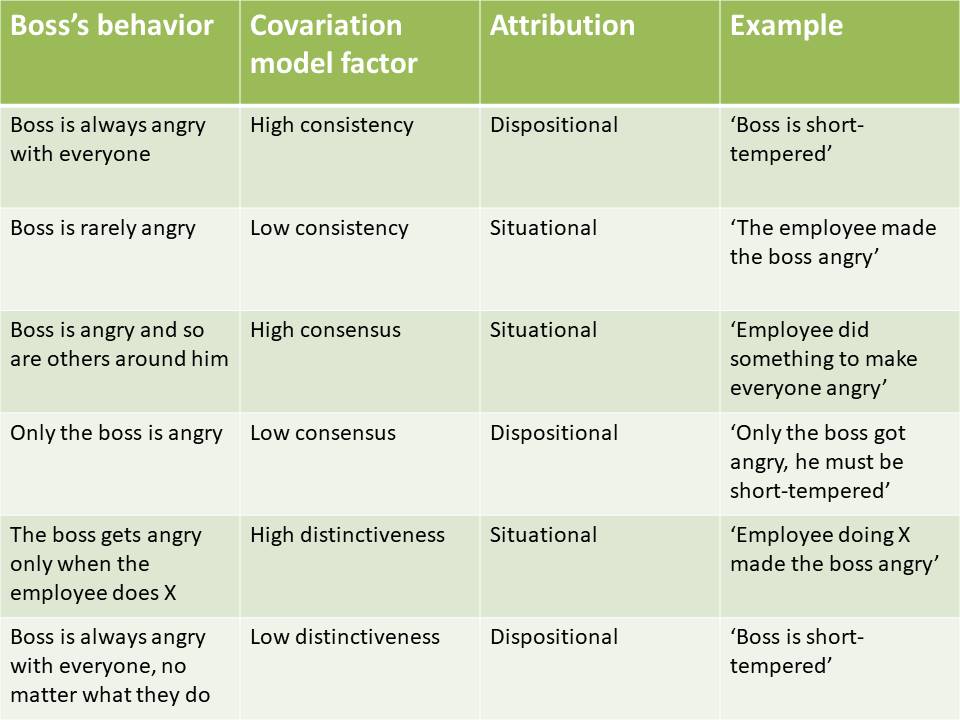

The covariation model of attribution theory helps us understand why people make dispositional or situational attributions. It says that people note the covariation of behaviors with time, place, and the target of behavior before making attributions.

Why did you conclude the boss is short-tempered? Of course, it’s because his behavior was consistent. That fact alone tells you that situations have less of a role to play in his angry behavior.

According to the covariation model, the boss’s behavior had high consistency. Other factors that the covariation model looks at are consensus and distinctiveness.

When a behavior has high consensus, other people are doing it too. When a behavior has high distinctiveness, it is done only in a particular situation.

The following examples will make these concepts clear:

- The boss is angry with everyone at all times (high consistency, dispositional attribution)

- The boss is rarely angry (low consistency, situational attribution)

- When the boss is angry, others around him are angry too (high consensus, situational attribution)

- When the boss is angry, no one else is (low consensus, dispositional attribution)

- The boss is only angry when an employee does X (high distinctiveness, situational attribution)

- The boss is angry all the time and with everyone (low distinctiveness, dispositional attribution)

You can see why you concluded that the boss is short-tempered in scenario 2 above. According to the covariation model, his behavior had high consistency and low distinctiveness.

In an ideal world, people would be rational, run others’ behavior through the above table, and then arrive at the most likely attribution. But this doesn’t always happen. People often make attributional errors.

Fundamental attribution error

Fundamental attribution error means making an error in the attribution of causation to behavior. It occurs when we attribute behavior to dispositional factors, but situational factors are more likely, and when we attribute behavior to situational factors, but dispositional factors are more likely.

Though this is fundamental attribution error, it seems to occur in some specific ways. People seem to have a greater tendency to attribute the behavior of others to dispositional factors. On the other hand, people attribute their own behavior to situational factors.

“When others do something, that’s who they are. When I do something, my situation makes me do it.”

People don’t always attribute their own behaviors to situational factors. A lot depends on whether the outcome of behavior is positive or negative. If it’s positive, people will take credit for it, but if it’s negative, they will blame others or their environment.

This is known as the self-serving bias because, either way, the person is serving themselves by building/maintaining their own reputation and self-esteem or harming the reputation of others.

So we can also understand the fundamental attribution error as the following rule:

“When others do something wrong, they’re to blame. When I do something wrong, my situation is to blame, not me.“

Fundamental attribution error experiment

Modern understanding of this error is based on a study conducted in the late 1960s in which a group of students read essays about Fidel Castro, a political figure. These essays were written by other students who either praised Castro or wrote negatively about him.

When readers were told that the writer had chosen the type of essay to write, positive or negative, they attributed this behavior to disposition. If a writer had chosen to write an essay praising Castro, the readers inferred that the writer liked Castro.

Similarly, when writers chose to derogate Castro, the readers inferred the former hated Castro.

Interestingly, the same effect was found when the readers were told that the writers were randomly selected to write either in favor of or against Castro.

In this second condition, the writers had no choice regarding the essay type, yet the readers inferred that those who praised Castro liked him and those who didn’t, hated him.

Thus, the experiment showed that people make erroneous attributions about the disposition of other people (likes Castro) based on their behavior (wrote an essay praising Castro) even if that behavior had a situational cause (was randomly asked to praise Castro).

Fundamental attribution error examples

When you don’t get a text from your partner, you assume they’re ignoring you (disposition) instead of assuming that they might be busy (situation).

Someone driving behind you honks their car repeatedly. You infer they’re an annoying person (disposition) instead of assuming they might be in a hurry to reach the hospital (situation).

When your parents don’t listen to your demands, you think they’re uncaring (disposition), instead of considering the possibility that your demands are unrealistic or harmful to you (situation).

What causes fundamental attribution error?

1. Perception of behaviour

Fundamental attribution error arises from how we perceive our own behavior and the behavior of others differently. When we perceive the behavior of others, we essentially see them moving while their environment stays constant.

This makes them and their action the center of our attention. We don’t attribute their behavior to their environment because our attention is diverted away from the environment.

On the contrary, when we perceive our own behavior, our internal state seems constant while the environment around us changes. Therefore, we focus on our environment and attribute our behavior to its changes.

2. Making predictions about behavior

Fundamental attribution error lets people gather information about others. Knowing as much as we can about others helps us make predictions about their behavior.

We’re biased to collect as much information about other people as possible, even if it leads to errors. Doing so helps us know who our friends are and who aren’t; who treat us well and who don’t.

Hence, we’re quick to attribute negative behavior in others to their disposition. We consider them guilty unless we’re convinced otherwise.

Over evolutionary time, the costs of making an erroneous inference about a person’s disposition were higher than the costs of making an erroneous inference about their situation.1Andrews, P. W. (2001). The psychology of social chess and the evolution of attribution mechanisms: Explaining the fundamental attribution error. Evolution and Human Behavior, 22(1), 11-29.

In other words, if someone cheats, it’s better to label them a cheater and expect them to behave the same way in the future than to blame their unique situation. Blaming someone’s unique situation tells us nothing about that person and how they’re likely to behave in the future. So we’re less inclined to do so.

Failing to label, derogate, and punish a cheater will have more drastic future consequences for us than wrongly accusing them, where we have nothing to lose.

3. “People get what they deserve”

We’re inclined to believe that life is fair and people get what they deserve. This belief gives us a sense of security and control in a random and chaotic world. Believing that we’re responsible for what happens to us gives us a sense of relief that we have a say in what happens to us.

The self-help industry has long exploited this tendency in people. There’s nothing wrong in wanting to comfort ourselves by believing we’re responsible for everything that happens to us. But it takes an ugly turn with fundamental attribution error.

When some tragedy befalls others, people tend to blame the victims for their tragedy. It’s not uncommon for people to blame victims of an accident, domestic violence, and rape for what happened to them.

People who blame the victims for their misfortunes think that by doing so, they somehow become immune to those misfortunes. “We’re not like them, so that’ll never happen to us.”

The ‘people get what they deserve’ logic is often applied when sympathizing with the victims or blaming the real culprits leads to cognitive dissonance. Providing sympathy or blaming the real culprit goes against what we already believe, causing us to somehow rationalize the tragedy.

For example, if you voted for your government and they implemented bad international policies, it’ll be hard for you to blame them. Instead, you’ll say, “Those countries deserve these policies” to reduce your dissonance and reaffirm your faith in your government.

4. Cognitive laziness

Another reason for the fundamental attribution error is that people tend to be cognitively lazy in the sense that they want to infer things from mthe inimum available information.

When we observe the behavior of others, we have little information about the actor’s situation. We don’t know what they’re going through or have been through. So, we attribute their behavior to their personality.

To overcome this bias, we need to gather more information about the situation of the actor. Gathering more information about the actor’s situation requires effort.

Studies show that when people have less motivation and energy for processing situational information, they commit the fundamental attribution error to a greater degree.2Gilbert, D. T. (1989). Thinking lightly about others: Automatic components of the social inference process. Unintended thought, 26, 481.

5. Spontaneous mentalization

When we observe the behavior of others, we assume those behaviors are the products of their mental states. This is called spontaneous mentalization.

We have this tendency because people’s mental states and actions often correspond. Hence, we consider the actions of people reliable indicators of their mental states.

Mental states (such as attitudes and intentions) are not the same as dispositions in the sense that they’re more temporary. However, consistent mental states over time can indicate lasting dispositions.

Research suggests that the process of spontaneous mentalization could be behind the tendency of people to attribute behavior to dispositional rather than situational causes.3Moran, J. M., Jolly, E., & Mitchell, J. P. (2014). Spontaneous mentalizing predicts the fundamental attribution error. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 26(3), 569-576.

Is it situation or disposition?

Human behavior is often the product of neither situation nor disposition alone. Rather, it’s the product of the interaction between the two. Of course, there are behaviors where a situation plays a greater role than disposition and vice versa.

If we are to understand human behavior, we ought to try to think beyond this dichotomy. Focusing on one factor is often done at the peril of ignoring another, resulting in incomplete understanding.

Fundamental attribution error can be minimized, if not completely avoided, by remembering that situations have a key role to play in human behavior.