A traumatic experience is an experience that puts a person in danger. We respond to trauma with stress. Prolonged traumatic stress can have significant negative psychological and physiological effects on a person.

Trauma may be caused by a single event, such as the loss of a loved one, or by continuous stress over time, such as living with an abusive partner.

Events that can cause trauma include:

- Physical abuse

- Emotional abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Abandonment

- Neglect

- Accident

- Loss of a loved one

- Illness

Traumatic stress generates defensive responses in us so we can protect ourselves from danger. We can broadly group these responses into two types:

A) Active responses (promote action)

- Fight

- Flight

- Aggression

- Anger

- Anxiety

B) Immobility responses (promote inaction)

- Freeze

- Faint

- Dissociation

- Depression

Depending on the situation and the type of threat, one or more of these defensive responses may be triggered. The goal of each of these responses is to ward off the danger and promote survival.

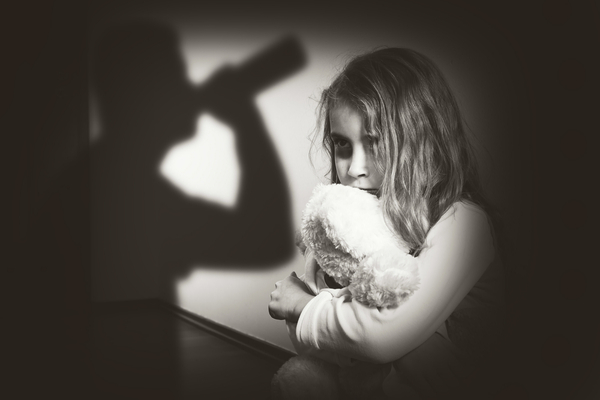

Why childhood trauma is especially damaging

Dissociation

Children are weak and helpless. When they go through a traumatic experience, they can’t defend themselves. In most cases, they can neither fight nor flee from threatening situations.

What they can- and usually do- to protect themselves, is to dissociate. Dissociation means splitting away of one’s consciousness from reality. Because the reality of abuse and trauma is painful, children dissociate from their painful emotions.

Developing brains

The brains of young children develop at a faster rate, which makes them highly vulnerable to environmental changes. Children need adequate and consistent love, support, care, acceptance, and responsiveness from their caregivers for healthy brain development.

If such adequate and consistent care is absent, it amounts to a traumatic experience. Trauma in early childhood sensitizes a person’s stress response system. That is, the person becomes highly reactive to future stressors.

This is a survival mechanism of the nervous system. It goes into overdrive to make sure the child is protected from danger as much as possible, now and in the future.

Emotional suppression

Many families don’t encourage children to talk about their negative experiences and emotions. As a result, children in such families never get a chance to express, process, and heal their traumas.

Unsurprisingly, parents are often the primary source of trauma for young children. Thanks to their inadequate and inconsistent care, children develop attachment and stress regulation problems that they carry into adulthood.1

Effects of childhood trauma

When children are abused or don’t receive adequate and consistent care, they develop attachment problems. They become insecurely attached to their parents and carry this insecurity into their adult relationships.2

As adults, they have difficulty trusting others and get anxiously attached to their romantic partners. They suffer from stress regulation problems. They’re easily stressed and resort to unhealthy ways of coping.

Also, they tend to suffer from constant worry and anxiety. Their nervous system is constantly on the lookout for danger.

If the childhood trauma is severe, they suffer from what’s called Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). It’s an extreme condition where a person experiences excessive fear, anxiety, intrusive thoughts, memories, flashbacks, and nightmares related to their trauma.3

What many don’t realize is that PTSD symptoms exist on a spectrum. If you’ve experienced even mild trauma in childhood, you’re likely to experience mild PTSD symptoms.

You may experience fear and anxiety, but not too much to disrupt your day-to-day life. You may experience intrusive thoughts, mini-flashbacks, and occasional nightmares related to your trauma.

For example, if a parent was overly critical of you throughout your childhood, it’s a form of emotional abuse. You may experience some mild PTSD symptoms as an adult, such as being anxious in the parent’s presence.

Their intrusive, critical voice haunts you and becomes your own critical self-talk. You may also experience mini-flashbacks of them criticizing you when you make mistakes or important decisions. (Take the Childhood trauma questionnaire)

Habituation and sensitization

Why do childhood traumas haunt people in adulthood?

Imagine you’re working at your desk. Someone comes up to you from behind and is like “BOO”. Your mind senses you’re in danger. You get startled and jump in your seat. This is a simple example of a flight stress response. Jumping in your seat or flinching is a way to avoid the source of danger.

Because you soon learn that the danger isn’t real, you relax back into your chair and restart your work.

The next time they try to startle you, you’re less startled. Eventually, you won’t be startled at all and may even roll your eyes at them. This process is called habituation. Your nervous system gets habituated to the same recurring stimulus.

The opposite of habituation is sensitization. Sensitization occurs when habituation is inhibited. And habituation is inhibited when the danger is real or too great.

Imagine the same scenario again. You’re working on your desk, and someone puts a gun on the back of your head. You experience intense fear. Your mind goes into overdrive and desperately searches for a way out of the danger.

This event has the potential to traumatize you because the danger is real and great. Your nervous system can’t afford to get habituated to it. Instead, it gets sensitized to it.

You become hypersensitive to any similar future dangers or stimuli. The sight of a gun creates panic in you and you get flashbacks about the event. Your mind keeps replaying the traumatic memory so you can be better prepared and learn important survival lessons from it. It believes you’re still in danger.

The way to heal trauma is to convince your mind you’re no longer in danger. It starts with acknowledging the trauma. Part of the reason a traumatic event keeps playing over and over in the mind is that it hasn’t been acknowledged and meaningfully processed.

Ways to heal childhood trauma

1. Acknowledgment

For many people, childhood trauma is like a tab in the browser of their minds that they just can’t seem to close. It remains open and frequently distracts and pulls on their attention. It warps their perception of the world and makes them overreact to non-threatening situations.

It’s a darkness inside them that’s simply there and doesn’t go away.

Yet, if you ask them to describe their traumatic experiences, they tend to have great difficulty doing so. This is because a traumatic event is highly emotional and shuts down the logical, language-based areas of the brain.4

In fact, all intensely emotional experiences tend to have the same effect. Hence the phrases:

“I was left speechless.”

“I can’t put into words how it felt.”

Because of this phenomenon, people rarely have a verbal memory of their trauma. If they don’t have a verbal memory, they can’t think about it. If they can’t think about it, they can’t talk about it.

This is why uncovering past traumas may require some digging and asking people who may have a better recollection of what happened.

2. Expression

Ideally, you want to consciously acknowledge and then verbally express your childhood trauma. People who haven’t yet made their trauma conscious tend to express it unconsciously.

They’ll write books, make movies, and create art to give shape to their traumas.

Expressing your trauma, consciously or unconsciously, gives life to it. It gives you an opportunity to express how you feel. Those emotions that have long been suppressed crave expression and release.

Thus, writing and art can be effective ways of healing trauma.5

3. Processing

Expression of trauma may or may not involve successful processing of it. The goal of repeated expression of trauma is to process it.

Traumatic memories are usually unprocessed memories. That is, you haven’t made sense of them. You haven’t attained closure. Once you attain closure, you can put that memory in a box in your mind, lock it, and shelf it away.

Processing trauma largely involves verbal processing. You try to understand what happened and why- the why being more important. Once you understand the why, you’re likely to gain closure.

Closure can be attained by simply understanding the trauma, forgiving your abuser, or even seeking revenge.

4. Seeking support

Humans are wired to turn to social support to regulate their stress. This starts in infancy when a baby cries and seeks comfort from the mother. If you can share your trauma with others who will understand, you lighten your burdens.

It gives you that “I don’t have to deal with this alone” feeling. Knowing that others are suffering, too, makes you feel slightly better about yourself.

Trauma impedes our ability to form connections. Creating new connections is, therefore, an important part of trauma recovery.6

5. Rationality

Trauma makes people emotional. Their perception changes, and they become sensitive to trauma-related cues. They see the world through the lens of their trauma.

For example, if you experienced neglect as a child and feel a deep sense of shame, you’ll blame yourself for your failed adult relationships.

By understanding your own traumas and realizing how they affect you, you can change gears in your head every time you’re in the grip of strong trauma-induced emotions. The more you understand your own ‘hot buttons’, the less you’ll be affected when someone presses them.

For example, if you’re a heterosexual short man and have been bullied about it, it’s likely to become your hot button. To heal from such trauma, you need to look at the situation rationally.

Since you can’t do anything about your height, you need to accept it. Once you truly accept it, you overcome it.

Acceptance needs to be based on reality for it to work. You can’t tell yourself:

“Being short is attractive.”

The reality is that women do have a preference for tall men. You can instead say:

“I have other attractive qualities that more than make up for my shortness.”

Since overall attraction isn’t based on a single feature but a host of features, this line of reasoning works.

6. Overcoming trauma-related fears

The most effective way to teach your brain that you’re no longer in danger is to overcome your trauma-related fears. Unlike ordinary fears, trauma-related fears are especially hard to overcome.

For example, if you’ve never driven a car, you may feel some fear and anxiety when you drive for the first few times. It’s just something you’ve never done before and your fear only stems from that.

If you get into an accident during those first few driving trials, your fear of driving becomes much stronger and harder to overcome. Now, your fears stem from inexperience plus an additional layer of trauma.

In this way, your trauma-related fears can prevent you from reaching important life goals.

Say you’re a woman who was abused in childhood by your father. Just because your father was abusive doesn’t mean that all men are abusive. Yet, your mind wants you to think that so it can better protect you.

In order to overcome such trauma-based fears, start looking at what people, situations, and things you tend to avoid. If you avoid something repeatedly, it’s a good indication there’s some trauma attached to it.

Next, start overcoming your fear by engaging with what you’ve been avoiding in baby steps. Force yourself to do the things you normally avoid. The more you go in the direction of your fears, the more your traumas will lose their power over you.

Eventually, you’ll be able to teach your mind that you’re no longer in danger.

References

- Dye, H. (2018). The impact and long-term effects of childhood trauma. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 28(3), 381-392.

- Nelson, D. C. working with children to heal interpersonal trauma: the power of play. THERAPY, 20(2).

- Van der Kolk, B. A. (1994). The body keeps the score: Memory and the evolving psychobiology of posttraumatic stress. Harvard review of psychiatry, 1(5), 253-265.

- Bloom, S. L. (2010). Bridging the black hole of trauma: The evolutionary significance of the arts. Psychotherapy and Politics International, 8(3), 198-212.

- Malchiodi, C. A. (2015). Neurobiology, creative interventions, and childhood trauma.

- Herman, J. L. (2015). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence–from domestic abuse to political terror. Hachette uK.