The human mind is a forgetting machine. We’ve forgotten most of the things that we’ve ever come across.

The mind is always trying to forget stuff because it has to make space for new items. Memory storage takes up resources, so memory needs to be constantly cleaned up and updated.1

Research shows that the conscious part of the brain actively reduces access to memories.2

This is because the conscious mind needs to free itself for new experiences and to make new memories.

Attention is a limited resource too. If all your conscious attention was fixated on memories, you’d be hindered from new experiences.

Despite this, why do we hold on to some memories?

Why does the mind sometimes fail at forgetting?

Why are we unable to forget some people and experiences?

When remembering trumps forgetting

Our minds are designed to remember important things. The way we ascertain what’s important to us is through our emotions. So, the mind tends to hold on to memories that have an emotional significance for us.

Even if we want to forget something consciously, we can’t. There’s often a conflict between what we consciously want and what our emotion-driven subconscious wants. More often than not, the latter wins, and we cannot let go of some memories.

Studies confirm that emotions can short-circuit our ability to forget things we’d most like to forget.3

We’re not able to forget some people because they’ve had an emotional impact on us. This emotional impact may be either positive or negative.

Positive emotional impact

- They loved you/You loved them

- They cared about you/You cared about them

- They liked you/you liked them

Negative emotional impact

- They hated you/You hated them

- They hurt you/You hurt them

The mind’s priority chart for memory

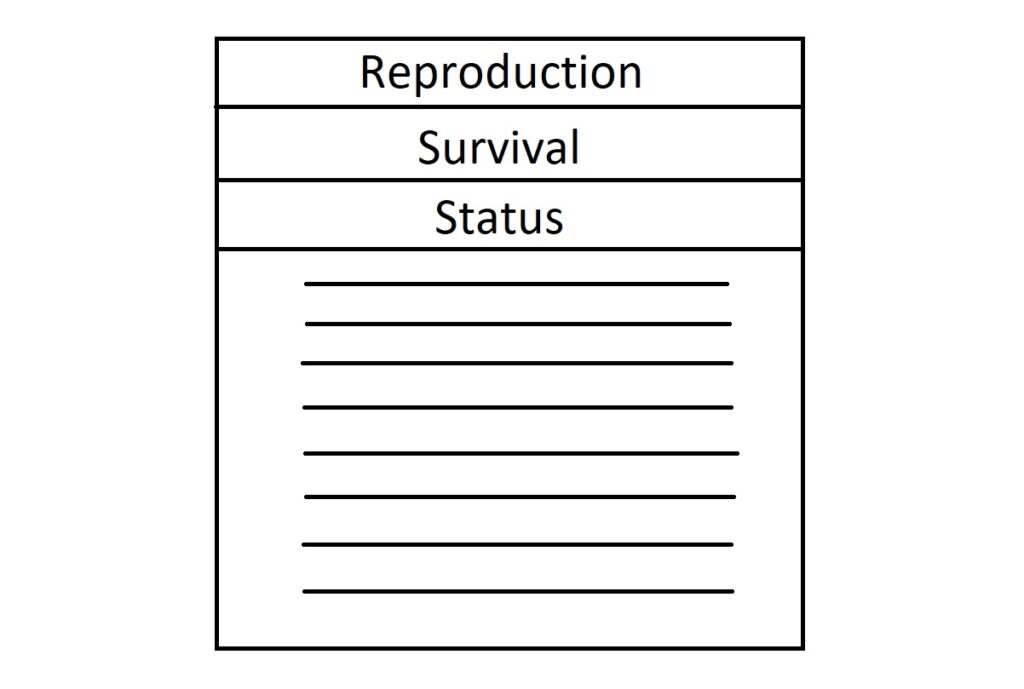

Given that storing memory takes up mental resources and the memory database is constantly updated, it makes sense that the mind prioritizes the storage of important (emotional) information.

Think of the mind as having this priority chart of memory storage and recall. The items associated with things near the top of the chart are most likely to be stored and recalled. The things near the bottom are hardly stored and easily forgotten.

As you can see, things having to do with reproduction, survival, and social status are more likely to be stored and recalled.

This is how the mind’s priority chart is organized. You can’t prioritize it your way. The mind values what it values.

Note that the items near the top of this chart often have to do with other people. When others facilitate your survival, reproductive success, or social status, they have a positive emotional impact on you.

When they threaten your survival, reproduction, and status, they have a negative emotional impact on you.

This is why you find it hard to forget people you like, have a crush on, care about, or love. In trying to remember these people, your mind is trying to aid your survival, reproduction, and status through positive emotions.

It’s also why you find it hard to forget people you hate or who hurt you. In trying to remember these people, your mind is trying to help your survival, reproduction, and status through negative emotions.

Positive emotions

- You keep thinking about your crush because your mind wants you to approach them (and eventually reproduce).

- You loved your parents as a kid because it was necessary for your survival.

- You can’t stop thinking about how your boss praised you in the meeting (raised your social status).

Negative emotions

- You keep thinking about the kid who bullied you in school years later (threatened survival and status).

- You can’t get over a recent breakup (threatened reproduction).

- You can’t forget the boss who insulted you in front of your colleagues (status threat).

How to forget someone: Why empty advice doesn’t work

Now that you understand what goes on when you can’t forget someone, you’re better equipped to handle such situations.

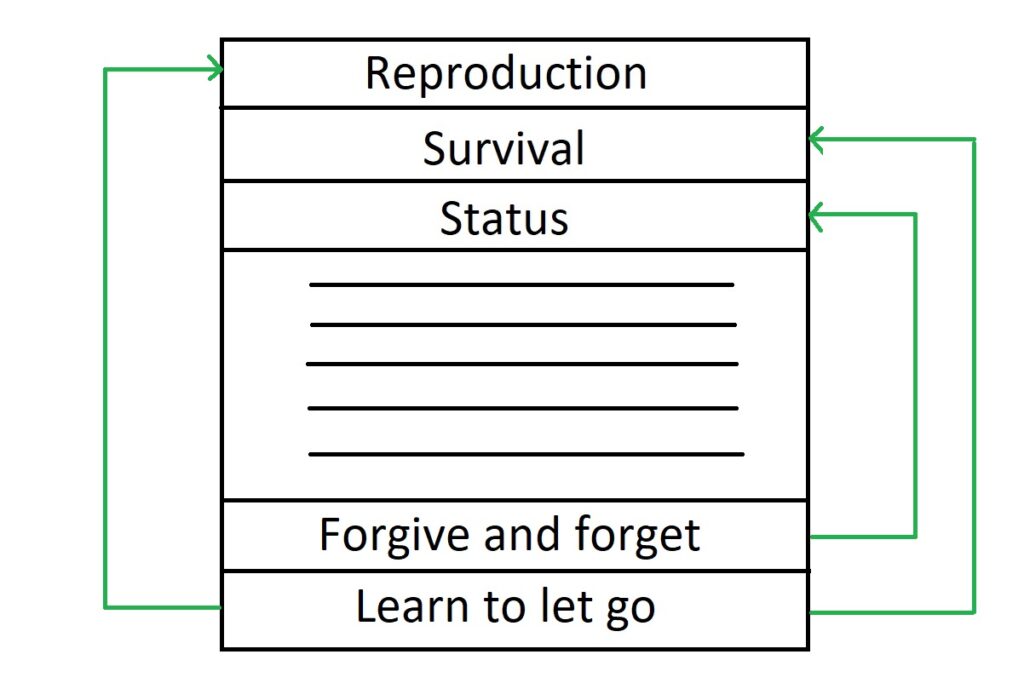

The problem with most advice out there about forgetting people is that it’s empty.

If you’re going through a rough breakup, people will give you empty advice such as:

“Get over him/her.”

“Forgive and forget.”

“Move on.”

“Learn to let go.”

The problem with these well-intentioned pieces of advice is that they fall flat onto your mind. Your mind doesn’t know what to do with them because they’re irrelevant to the top items in its priority chart.

The key to forgetting people and moving on, then, is to link these empty pieces of advice to what the mind values.

When you’re going through a breakup, something important in your life has ended. There’s a gaping hole in your life. You can’t just ‘move on’.

Say a friend tells you something like this:

“You’re at a point in your life where you should focus more on your career. When you get established, you’ll be better positioned to find a relationship partner.”

See what they did there?

They linked ‘moving on now’ to ‘being better-positioned later to find a partner’, which is at the top of the mind’s priority chart. This advice is by no means empty and could work because it uses what the mind values against the mind.

Say you’re mad at someone because they humiliated you in public. You keep thinking about this person. They’ve taken over your mind. While showering, you think about what you should’ve said back to them.

At this point, if someone tells you to ‘forgive and forget’, it’ll likely piss you off. Consider this advice instead:

“The guy who was rude to you has a reputation for being rude. He’s probably been hurt by someone in the past. Now he’s lashing out at innocents.”

This advice frames the guy as a hurt individual who can’t get over their issues- precisely what your mind wants. Your mind wants to raise you in status compared to him. They’re hurt, not you. No better way to put him down than to think he’s been hurt.

More examples

I’m trying to think of some unconventional examples to elucidate this concept further. Ideally, you want your relationship partner to satisfy all the important items on the priority chart.

A woman who’s married to a mafia boss, for instance, may have her reproductive and status needs met, but her survival could constantly be in danger.

If her survival was constantly under threat while she was with him, she might finally be relieved to break up with him. It’ll be easy for her to move on.

Similarly, you could constantly be thinking about your crush, but one negative piece of information about them could threaten your top item. And it won’t take long for you to move from them.

A big part of why people cannot forget those they’ve broken up with is that they think they can’t find someone similar or better. Once they do, they can move on as if nothing happened.

If you want to forget people who’ve hurt you in the past, you need to give your mind a solid reason why it should bury the hatchet. Ideally, that reason should be based on reality.

Importance leads to bias

Because survival, reproduction, and status are so crucial to the mind, it tends to get biased in these matters.

For example, when you’re going through a breakup and missing your ex, you’re likely to overfocus on only the good bits of the relationship. You want to re-live those memories while forgetting that there were negative sides to the relationship too.

Similarly, it can be easy to perceive neutral behavior as rude because, as social species, we’re on the lookout for enemies or those who threaten our status.

If a car cuts you off, you’re likely to think the driver is a jerk. It could be they’re in a rush, trying to get to an important meeting.

References

- Popov, V., Marevic, I., Rummel, J., & Reder, L. M. (2019). Forgetting is a feature, not a bug: intentionally forgetting some things helps us remember others by freeing up working memory resources. Psychological science, 30(9), 1303-1317.

- Anderson, M. C., & Hulbert, J. C. (2021). Active forgetting: Adaptation of memory by prefrontal control. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 1-36.

- Payne, B. K., & Corrigan, E. (2007). Emotional constraints on intentional forgetting. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(5), 780-786.